Students Travel to Prague and Vienna to Learn About Nuclear Reactors

| by Nadia Pshonyak

Students had the chance to visit multiple facilities and meet with experts at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Your mission, should you choose to accept it: Manage an international crisis that threatens to launch China and the U.S. into nuclear war—with emerging technologies, like artificial intelligence, potentially creating new risks of escalation.

That’s not the typical email that lands in graduate students’ inboxes.

But so it went for several Institute students who just so happen to study things like AI, nuclear nonproliferation, and international relationships (in general) and China (in particular).

“As an expert in national security, your participation is key to the success of this simulation and research project and, ultimately, to the success of efforts to create policies, capabilities, and legislation that ensures international stability and minimizes the risks associated with interstate conflict,” the email read.

Decker Eveleth, who is completing his master’s degree in nonproliferation and terrorism studies, was among those who accepted the invite.

“We do have a lot of interesting opportunities here at Middlebury,” he said.

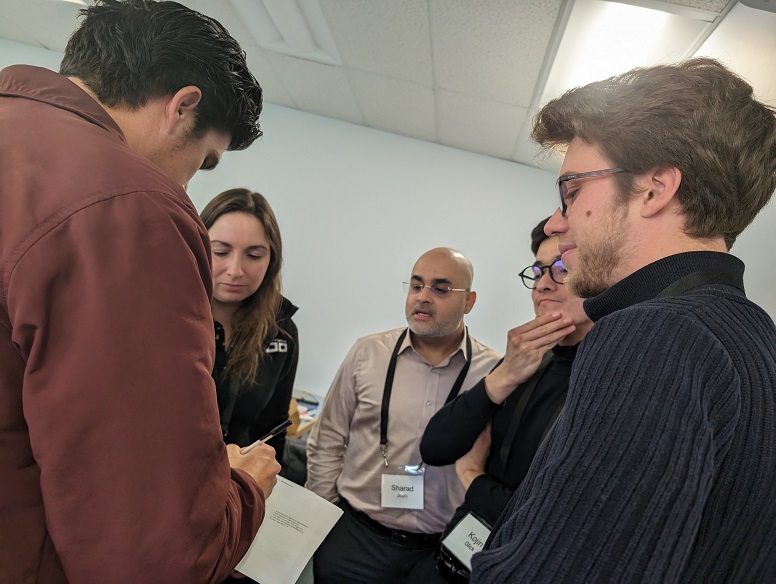

About 25 people participated in the daylong exercise hosted on the Institute campus, which was co-sponsored by the Institute’s Cyber Collaborative and James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Participants were given a hypothetical high-stakes scenario—involving China posturing to attack Taiwan—and a briefing on relevant capabilities and threats. Then they formed teams to develop a response plan.

Jacquelyn Schneider with the Hoover Institution led the exercise with the project’s director, Harold Trinkunas, the senior research scholar at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Schneider served as an Air Force officer in Korea and Japan and is the director of the Hoover Institute’s Wargaming and Crisis Simulation Initiative. Much of her work zeroes in on the intersection of technology, national security, and political psychology—with plenty of cybersecurity, autonomous technologies, wargames, and Northeast Asia elements as well.

“We came to Middlebury because we knew there is a concentration of students who are top-notch, in a community with a lot of people who work in international security,” she said.

Experts deep into their careers also joined the games, including Erik J. Dahl, associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, just up the road from the Institute.

“War games and other practical exercises provide a great opportunity for graduate students to put into practice what they are learning and also to meet outside scholars and practitioners whom they might not otherwise get to work with,” he said. “The benefit for the MIIS students is both short term, because it helps make what they learn in their courses come alive, but also in the longer term, because they can make contacts and develop skills they’ll be using later on in their professional lives.

It’s an incredible way to learn about how everything in a complex situation can best be managed. It’s not using the wargame as a predictive tool, but making people think about the factors that matter most when a crisis really comes.

Professor Sharad Joshi, who teaches global politics and security at the Institute, also joined in. He emphasized how practical the exercise proved.

“It’s not something we are dreaming up out of the blue,” he said. “A slow burn in relations [with China] has been taking place over the last three or four years, so this is as real world as it gets.”

Many Institute students may go on to face real scenarios in their careers that are not that different from those they practice in the games. Nearly half go into jobs in the government or at intergovernmental organizations, with many at private companies or NGOs that work at the intersection of complex public-private security issues.

The simulation discussions proved robust, with participants surfacing both practical and profound questions:

How do you address the use of a technology that some policymakers don’t understand?

What are the best ways to prioritize diplomacy, sanctions, and cyber warfare?

Why are rules of engagement important for both humans and robots?

“Even if AI is more accurate,” one participant interjected, “I still want a human to deploy a weapon so I have someone to hold accountable.”

As the exercise unfolded, Middlebury students drew plenty of insights applicable to their future global security careers.

Eveleth reflected, “It’s an incredible way to learn about how everything in a complex situation can best be managed. It’s not using the wargame as a predictive tool, but making people think about the factors that matter most when a crisis really comes.”

| by Nadia Pshonyak

Students had the chance to visit multiple facilities and meet with experts at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

| by Mark C. Anderson

A multidisciplinary group of Institute students traveled to D.C. to present the AI tool they developed in the national finals of Invent2Prevent.

| by Sierra Abukins

If you need to find some hope in these dark times, tune in to Professor Jeffrey Lewis’s podcast highlighting unsung heroes preventing global catastrophe.